There are some critical points that separate the psychedelic from the theological and make it worthy of our attention. For one, as I’ve previously mentioned, the psychedelic experience is a valid epistemological tool unlike theology. To put it in terms we’ve already encountered, theology is firmly in the realm of consensual reality. This means that it has no effect on us if we stop believing in it. This is why it’s pointless to threaten atheists with hell or eternal reincarnation- it’s like telling an adult that Santa Claus is watching. Hence, most of us realize the ‘transcendent truths’ only of our parents’ religion, which is likely our religion. But the psychedelic experience is a component of objectively reality. The right amount of the right psychedelic is certain to have an effect on you. As we will see, that effect will be a result of several factors. But what’s certain is that an effect will take place. This is why speculations that draw from psychedelic experiences are worthy of being entertained. There exists a debate on whether what we see in deep states of psychedelia is an external world or an internal one, and we will explore this issue to its merit. But settling down on either side of the debate does not reduce the importance of the psychedelic experience.

Before we see what psychedelically-derived speculations have to offer, let us undertake a short history and description of the psychedelic experience, including my own initiation. Not counting cannabis, my first experience with the psychedelic was through five grams of psilocybin mushrooms, in the company of friends in Canada, 2004. While I’ve been more judicious in my psychedelic usage since, I took those mushrooms knowing only that they would make me see cool colours and fractals inside my head. Indeed, that is how it started. We were listening to Led Zeppelin, and around forty-five minutes after I had ingested the mushrooms I could close my eyes and see zany flickers of multi-coloured lightning flash in my head in correspondence with Jimmy Page’s riffs. I enjoyed those innocuous sensations for a while before I had the idea to re-watch an old classic- Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

I bid my friends farewell, and I remember the strange feeling upon us as we dispersed one by one. There was a Lord of the Rings sort of vibe, where each of us were off to our respective quests with the promise of reuniting when it was all over. There was a lot of hobbit-like giggling and snickering involved, with one friend refusing to come out from below the table, which he insisted was a most snug and secure spot to settle into. I reached my hostel room and put on the movie as planned, keeping pen and paper at hand as a friend suggested. I’d seen the movie twice before, but as I saw it again on mushrooms it acquired a whole new layer. There was meaning in it I had never seen before, interspersed with nuggets of geometry, information and colour that I could reach out to by closing my eyes. I remember scribbling a few things on the paper, the contents of which were deep and personal in the moment but incomprehensible by the next day.

Once the movie was done, I moved to the comfort of my bed and wrapped myself in a blanket. For the next few hours I tripped- given to a seemingly time-dilated journey through sights so overwhelming that I was swept in the brilliance of what I beheld. Mushroom trips have their peaks and troughs. You reach a crescendo of tripping when suddenly the world you were in vanishes like dissipating fog. Is it done, you wonder. Is it over? Am I done tripping? But then it starts afresh and sweeps you up all over again, leaving you wondering the same thing at the next lull.

Around five hours into my trip, I had what I was convinced was an encounter with god. I had been searching for him (yes, I imagined him as a male) all my life, wavering between scepticism and a purely personal faith. But there he was in all his majesty, showing himself to be exactly as infinite, powerful and authoritative as I thought he would be. It was the best experience of my life. My most fundamental questions had been answered! I now knew the answer to life, the universe and everything- it was dazzling me with its omnipotence.

God scrutinised me just as mercilessly as a perfect being would, admonishing me for all my warts and faults. He ripped my consciousness open, showing me the useless creature I really was. How arrogant I had been until that point, how smugly secure in my pathetic existence. I even thought I could allow my ape-mind to doubt the existence of god! For all this, god decided that he would punish me. And punish me he did. As the next crescendo of that trip wound down, I emerged from my blanket again wondering whether it was all over. That was when I noticed something strange. My right hand was extraordinarily smaller than my left hand! I used to wear a ring on my right hand, and the ring fell cleanly off if I turned my hand upside down. I put the ring on my left hand, and it fit perfectly fine. But when I brought back it near my right hand, the hand looked laughably miniscule.

Worried, I stepped in front of the mirror and received a greater shock. My entire right side was shrunken, looking freakishly smaller than my left side. Right ear, right eyeball, right leg, even the right side of my tongue. All incompatibly smaller than my left side. I suddenly realised what had happened. To punish me, god had placed me in a different dimension. But something went wrong in the process, and I emerged in this dimension with my right side shrunken. I prayed to him- Okay, punish me. Place me in a different dimension, place me in any dimension. But wherever you send me, fix me. Don’t let me look like this! The prayer did not work, and so I called a friend who had taken mushrooms with me, seemingly ages ago. “Something’s wrong, man,” I told him on the phone. “I know,” he replied, “Something’s horribly wrong.”

On a trip of his own, he was of no help to me. But the short conversation with him served to remind me that this was just the drug. Only mushrooms, and I wasn’t really in another dimension. But then what about my atrophied right side? I decided to go out for a smoke, reasoning that a dose of tobacco should help ground me. Outside, just as I suspected, people stared at me. Who wouldn’t? My shrunken right leg and hand must have looked comic to anyone. Two cigarettes later I felt better, and my body was beginning to reacquire its human symmetry. Back in my room, a voice in my head conveyed through colourful geometry that this was only a warning.

Like Krishna demonstrated the power of infinity to Arjuna in the Mahabharata, I had been given a vision of the absolute. I now knew how it held sway over my life. And I was told to behave. Around eight hours after we all ingested the mushrooms, we re-converged in the original room. Lost in our own introspections, the soft melodies of Pink Floyd and Shpongle helped us put our trips in perspective. A Swedish friend, who was decidedly atheist, had also taken mushrooms for the first time that morning. I remarked to him- “Don’t you see it now? There is a god after all, and he is watching over each one of us.” My friend’s expression told me that he had a completely different sort of trip, and god had no appearance in it.

There have always been two elements to the psychedelic experience. The first is the experience itself, the practice part of the discipline. Then there is the theory, all the body of knowledge and literature that goes into interpretation of the practice. In traditionally tribal societies, the theory was given by the shaman- the central figure of humanity’s engagement with altered states of consciousness. We will learn more about shamans and psychedelic theory in later chapters, and as I have learnt and practiced more over the years I have come to understand my first psychedelic experience better.

The most terrifying and vividly remembered part of my trip was the atrophied right side of my body. The memory is so clear even now, more than a decade later- that’s how real it was back then. The horror on looking at myself in the mirror and seeing my right side freakishly shrunken. The helplessness of not being able to reason out of it by telling myself that it’s just a drug’s doing. Worrying that my ridiculously small right eyeball would pop out if I looked down. The phenomenon has a simple name- somatic hallucination. This is the sort of hallucination that plays with your physical perception of your body, and it manifests in various ways. Eyes seeming to float to other places on the face, abnormally sized limbs and appendages, anatomical disfigurations- if you’re seeing these sort of things, you’re having a somatic hallucination. You haven’t been flipped to another dimension.

While my somatic hallucination was obviously the most harrying on a physical level, philosophically nothing comes close to a perceived meeting with our maker. What explains that component of my experience? My interpretation of this has much to do with the therapeutic role some psychedelic compounds such as psilocybin and LSD can play in our lives. They facilitate a form of self-introspection our daily awareness is unable to generate. In a sense, they help us catch our own tails most effectively- they help us finally move on to wondering why we were trying to catch it in the first place! That’s introspection at the most existential level, and it’s why these compounds have repeatedly demonstrated effectiveness in treating a wide range of mental travails such as addiction, depression and trauma.

My own motivations at the time, as even now, were fundamental in nature. I wanted to know where everything came from. Why we existed, and to what end. The psilocybin showed me what I wanted to see. It told me that the question was not of catching my tail, it was of what I would do once I had caught it. Now you know, I imagine the psilocybin telling me. You’ve seen god and you’ve seen what you are. What next?

Not every psychedelic experience is like this, of course. Five grams of psilocybin mushrooms is a healthy dose, what the famous psychedelico Terence McKenna called a “hero’s dose”. Given my newbie status, it was more than enough to take me to the depths of psychedelia. In subsequent experiences I’ve learnt to be more conscious of what’s happening to me. More inquisitive, and more courageous. I’ve taken up to eight grams of mushrooms at a time, but with the right preparation and setting I’ve navigated through such experiences without the trauma of my first time.

When did humanity first experience the psychedelic? In his book Supernatural, Graham Hancock makes a strong case that the experience of altered states of consciousness has been with humanity since the beginning of our cultural and cognitive revolution. Even more, it has played a deep role in the very origin of language and symbolism. Hancock points us to a peculiar ‘before-and-after’ moment in human history, between 40,000 and 100,000 years ago. Before this moment, there is nothing in the archaeological record to differentiate us from other primate species. After this moment, signs of culture, language, art and architecture start appearing across the planet. Something happened that allowed us to use meaning and form in a way no other species can. And that something makes us human. To Hancock, it was our ancestors’ first dalliance with psychedelics that set them on the road to modern humans. Terence McKenna went as far as saying that human language itself is a lower derivative of the abstract meaning-space one enters in psychedelia, and rampant psychedelic usage is one of history’s worst kept secrets. Some observations in support of this assertion are:

- The Rig Veda, the oldest text of the Indian subcontinent and among the oldest in the world, frequently mentions a psychoactive substance called soma. Like most Sanskrit words, soma has more than one meaning. In one context it even refers to the moon, and the mythic Indian dynasty that claimed descent from the moon called itself Somavansha. We know enough to claim with certainty that one meaning of soma was a plant/substance that gave its users altered experiences of consciousness. A chronological reading of Hindu mythology suggests that the original soma was lost somewhere in time, replaced by lesser plants towards the same ritual purposes. There are many suggestions on what soma could have been, the most widely accepted is that it was the amanita muscaria mushroom, more commonly known as fly agaric. Amanita muscaria is not like psilocybin mushrooms, and its documented effects are often unpredictable and sometimes undesirable. One reason why soma could be fly agaric is that the Rig Veda mentions men urinating soma, which is then drunk by other men. It is a known characteristic of fly agaric that its psychoactive properties are passed along in urine. This is why the shamans of Siberia, who we know used fly agaric as their central psychoactive, also drank urine passed out after ingesting fly agaric. Other candidates offered for the identity of soma are ephedra, cannabis, psilocybin mushrooms and ayahuasca-analogues such as a mixture of peganum harmala (Syrian rue) which contains MAO-inhibitors and a phalaris grass which contains DMT. It’s also possible that different psychoactives were used at different points in time.

- For close to two thousand years, the Greek society held an annual event known as the Eleusinian Mysteries. Initiates from all over the Greeks’ known world converged once a year for a secret, religious rite of passage. Only murderers and those who could not speak Greek were disallowed from participation. Initiates were vowed to secrecy not to publicly talk of the rite. But there are still several known details of what this rite of passage entailed, one of which is the drinking of a substance known as the kykeon. There exists a strong case that the kykeon possessed a psychoactive substance. Like in the case of soma, there are many candidates for the identity of kykeon. Most contemporary theories offer an LSA-containing ergot that thrived as a parasite on barley, where LSA is an LSD-like compound. It’s possible that a central ritual of the Hellenic world, one that lasted for two millennia, contained the ingestion of a psychoactive substance as one of its core elements.

- The best surviving example of psychoactive usage can be found in the tribes of the New World. Ayahuasca, one of the most potent and profound psychedelics, is used by Peruvian tribes. Psilocybin mushroom was found central to the rituals of Mazatec Indians in Mexico. Mescaline-containing peyote is used by some Native North Americans to this day. There are of course several cultural differences in how each of these people approach their rituals. But attaining psychedelic states of consciousness through the ingestion of plants is a central ritual for all of them. Their shamans are experts of these realms, which these tribes readily claim are real, non-material only in their nature relative to us. Here we are met with the assertion that the deep psychedelic state is an experience of something beyond just between ape ears. These tribes claim that the psychedelic realms really exist, populated by entities both malevolent and benevolent. The shamans enter these realms and negotiate with the entities to bring knowledge, healing and guidance to their tribes.

- Forest-dwelling and hunter-gatherer African societies that survive to this day, such as the Bwiti, have tabernanthe iboga as their central psychoactive plant. This plant contains ibogaine, which is a psychoactive alkaloid like psilocybin and DMT. The Bwiti shaman is called N’ganga, and the crucial Bwiti initiation ceremony that every man undergoes involves the ingestion of iboga bark and sap. Taking iboga brings to the Bwiti both open and closed-eye visions, where they meet their past-life variants and also their ancestors. It is tempting, but not entirely valid, to extrapolate from one hunter-gatherer tribe and say that all ancient hunter-gatherer tribes used psychedelics in their central rituals. But examples such as the Bwiti tell us that nothing in the psychedelic experience itself exempts its early adoption by the most ancient homo sapiens.

The role that psychedelics could have played in human history is easier to see if we think in terms of the origin of religion. We like to imagine primitive humans making up explanations for things they did not understand. Violent thunderstorms hitting my village tonight, could it have something to do with the goat I killed yesterday? Neighbouring tribe attacking our village and enslaving us? Perhaps it’s because we did not honour the bison well during our last hunt. The desire to have better control over and awareness of their environment made ancient minds conjure various deities they could appeal to for intervention. Yuval Noah Harari sees religion as one of the many ‘belief-systems’ that originated in homo sapiens and gave them a leg up over other human species. It was our ability to collectively believe in certain things that allowed us to co-ordinate and organise on massive scales. Under this context, religion is just like money, democracy and human rights- things large groups of humans together accept as the truth. Harari calls them our inter-subjective reality, and we will discuss this idea in further detail in the chapter on our cultural universe.

But adding psychedelics to the equation gives us a different picture. If ancient humans were consuming psychedelic plants and having visionary experiences, then they did not make all this stuff up. They genuinely believed in it and constantly engaged with it. The supernatural world was as real to them as the material one. Imagine going back in time to 20,000 B.C. and consuming eight grams of psilocybin mushrooms on the eve of a massive thunderstorm. There would be no way for you to differentiate between what you’re seeing inside your head and what you’re seeing outside. In this set and setting, both are equally real to you. The same goes for the entire tribe if it consumes small doses of a psychedelic before invading an enemy tribe. The invaders’ ancestors will really be with them as they fight, guiding and protecting them. What this means is that psychedelics do not simply give us a glimpse of what lies behind humanity’s religious impulse- psychedelics inspired that impulse in the first place.

Let us now go back to that primitive woman we met at the beginning of this book. As she labours through narrow crevices, venturing deeper underground, she’s under the influence of a powerful visionary plant. If the plant contains DMT, she’s likely experiencing auditory hallucinations as well. Whether her eyes are open or closed, she encounters strange entities and senses the presence of other minds. These could be her own ancestors, powerful supernatural beings, or half-man and half-animal hybrids of various kinds. It doesn’t matter whether these things are compatible with the modern material worldview. What matters is that they are real to this woman. In fact, people often describe their experience on psilocybin or DMT as ‘more real than real,’ and I will attest to this in later chapters. To this woman then, what she sees in the silent darkness many meters underground is more real than real. These entities control and dominate her world more than atoms, molecules and compounds.

In the book Supernatural, after a thorough investigation worth a careful reading, Graham Hancock concludes that homo sapiens’ great cognitive leap forward was fuelled by psychedelics. The first languages, the first attempts at externalising meaning, these were feats our ancestors achieved using psychedelics. If Hancock is right, this means that psychedelics are as old as human culture itself. But even if he is wrong, we know that psychedelic usage is a pretty old habit any way. The cultural and legal repression of psychedelic usage is a modern phenomenon, born largely through fundamentalists and their dislike of substances that they either do not understand or that break down the cultural barriers they want to maintain.

This explains why alcohol, caffeine and nicotine are legal, but psilocybin, DMT and mescaline are not, when study after study proves the first group to be far more harmful to us. Take the example of a 2010 Lancet study in the UK on the harms of drugs. Researchers asked leading drug-harm experts to rank 20 legal and illegal drugs on 16 measures of harm, such as damage to health, economic costs and crime. Each drug was scored on a scale of 100, with higher scores implying higher levels of harm both to the users and to society. These were the results:

Alcohol was found most harmful by a wide margin, with a significant chunk of the harm inflicted on society. Look at the bottom end of the spectrum- LSD and mushrooms. Even if we allow for some correction basis the fact that alcohol and nicotine, being widely and legally available, simply get far more opportunity to harm society than psilocybin does, the wide difference suggested by the Lancet study is telling. Like Terence McKenna often said, psychedelics are illegal not becau isse a benevolent, protector state cares for you and does not want you to jump out of a window. Psychedelics are illegal because they challenge your belief in the cultural realities that institutions create and need erected to sustain themselves.

Even the drug peddling business illustrates the relatively benign effects of psychedelics. They are non-addictive, and it is tough to turn to psilocybin as regularly as one might to cannabis or cocaine, and in cases that you do it would have to be through micro-dosing. As a result, if you’re a drug peddler, it makes little sense for you to introduce your clients to a psychedelic. You’d rather hook them to substances that ensure that they keep coming back to you frequently and purchase large quantities. This explains why procuring cocaine in Delhi or Mumbai is a cinch but find someone who can sell you psilocybin mushrooms and I’ll show you a flying horse. A drug peddler who tries to expand his psilocybin mushrooms business is like a cigarette manufacturer who introduces nicotine-free cigarettes. There is certainly a flipside to this as well. A psychedelic as powerful as ibogaine could possibly cause one to go psychotic, and extremely large quantities of it are required to achieve a visionary state. A drug peddler selling ibogaine could possibly be left with delirious clients.

Thus, one shouldn’t get a rainbow picture of psychedelics. While they are far below many legal drugs in the amount of physical harm they can do, there exist serious dangers to psyche. The usage of psychedelics should be an informed and conscientious decision. My first psychedelic usage, for example, was an irresponsible act. I knew little to nothing about mushrooms and took the dose my friends suggested. I did not inquire to the authenticity of the substance or read up on how best to prepare for its ingestion. But that psychedelics have several positive benefits, that they have been used by humanity for a very long time, and that their modern criminalisation is more a product of propaganda and fear than social concern are facts that we cannot deny.

With this background, we can finally ask the question- what does psychedelia tell us on origin and cosmogony? Psychedelic cosmogony is closely tied with shamanistic cosmology, which in turn was developed by shamans through their association with altered states of consciousness. It is not possible in this book to do justice to shamanistic cosmology, which is as varied as the tribes that are shamanistic. So I will make generalisations, and I hope the culturally-sensitive can forgive me for missing nuances they undoubtedly find relevant. Shamanistic cosmology sees reality in three phases- the upper world, the middle world and the lower world. As the names might suggest, the upper world is the realm of the transcendent- things beyond material reality. Celestial, angelic and a better reflection of things, this is where helpful entities reside. This is also where our own better versions reside, the things we can become if we take the guidance seriously.

The middle world is us, here and now. The material and objective reality so wonderfully described to us by physics, chemistry and biology. It is to effect changes on this plane that shamans enter other realms, for the knowledge gained there is needed for healing, prediction, and guidance here. The lower world is the world below, inside us but not perceptible to everyday awareness. Here we store our repressed psyches, our fears, faults and guilts. The lower world is the realm we do not want to see, but it is also the realm we must face if we are to be expert navigators. True shamans usually conquer the lower world in their childhood, through a troubling and life-threatening experience such as illness to the brink of death. By the time they take their official role they know how to negotiate with all sorts of entities for their tribe’s benefit. Indeed, most shamans maintain that to be one, you need some form of natural talent. It cannot be cultivated.

In his book The Cosmic Serpent, anthropologist Jeremy Narby shares with us his conclusions after spending much time with the ayahuasca-ingesting shamans of Peru. His experiences have led him to the startling conclusion that DNA is intelligent and sapient, and that it has been consciously guiding the evolution of life since its origin. Recall here that Darwin acknowledged natural selection as the main but not exclusive means of variation. The minded-DNA theory steps into this gap and asserts that the variation of species, apart from adaptation to external conditions and from sexual selection, has also been guided by the intelligent hand of DNA which is in every lifeform. But as you read Narby’s book and come to see everything the Amazonian shamans have learnt from their plants and ayahuasca, you notice a glaring gap. For all their knowledge of minded-plant species, higher and lower forms of beings, and a conscious unifying entity among all of us (DNA), they seem to ask no questions on the ultimate issue of origin itself.

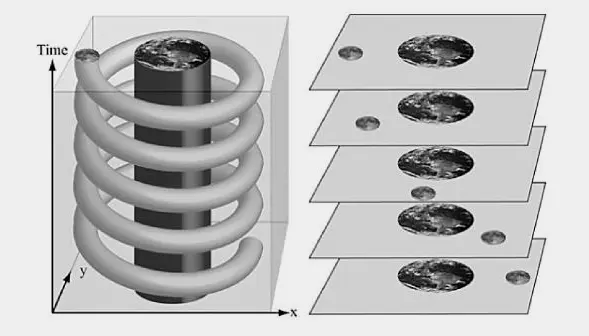

Narby relies on a panspermia interpretation, that life, or DNA, came to this planet from elsewhere- and I assume this seems to suffice for the shamans he learnt from as well. A deeper study of shamanistic thought reveals that it looks at existence, like Vedantins, Plato and Einstein did, as a static, eternal plane. It has always existed, and it will always exist. Only the flow of time creates the illusion of birth, death and causality. Plato called time the moving image of eternity, and Einstein said- “The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” The result is better understood through viewing this image, taken from Max Tegmark’s Our Mathematical Universe:

Look at the figure on the right first, which represents our view of time. We perceive time as some sort of a flow, hard-wired into our brains because we cannot move in time as we do in space. This is called the arrow of time, and it has forever pointed in one direction. Moving in time as freely as one does in space would be a supernatural act, and it is the darling child of science-fiction imagination. Each layer in the figure on the right represents one particular moment in time to us, and we call the layers above ‘future’ and the ones below ‘past’ much like we say, ‘ahead of me’ or ‘behind me.’

The figure on the left shows how time really is- just another component of spacetime. The flow creates an illusion of before and after, but both the past and the future are real and eternal, despite the confused perceptions of an ape mind. The difference between these images is the difference between viewing reality as a three-dimensional space where things change over time versus viewing it as a four-dimensional spacetime where nothing changes. Spacetime is infinite, and so there is no question of creation or destruction. Einstein’s equations confirm the mathematical truth of this, so one could argue that this confirms shamanistic cosmology. But then it confirms the Vedic concept of brahman as well, as it does any non-falsifiable concept of an eternal form. Besides, if we’re going by mathematical confirmations, then where are the equations that describe the upper and lower worlds?

What’s important to take home from shamanism is that concerns of creation and destruction are trivial compared to the here and now- where we reside and engage with reality. Indeed, this is what Vedantins, Plato and Einstein all realised. The flow of time is to blame for all our hand-wringing over the matter of causality and purpose. On its own, existence is eternal and infinite, and today/tomorrow are always as real as forward/backward. It is thus clear that all three worldviews- theological, scientific and speculative- insist that the question of creation is essentially without meaning. It’s a question born from ignorance, whereas the bird’s-eye view shows that there cannot be a birth or a death. In The Cosmic Serpent, Jeremy Narby tells us that the Peruvian shamans describe their secret, ayahuasca-inspired vocalisations not so much as ‘language’ but as ‘language-twisting-twisting’- a sort of doubling back of things upon themselves in a way that human language is unable to describe them. The root intuition behind this is extendable to the entire question of origin. What seems to us as the most pertinent query about existence, when doubled back on itself, is revealed as an illusion and an unnecessary obstacle to further understanding.

This is an important lesson in our quest- that the flow of time causes much unwanted illusion. Understanding this is essential in approaching closer to the meaning of life, the universe and everything. The necessary gap of knowledge shows how humans are fated to endlessly chase an upwards spiral of causality. But we have finally caught up with our tail. Theologically, scientifically, philosophically and psychedelically- we have approached the truth with the knowledge that time is nature’s way of having fun with us. When we stop perceiving its flow, as best as we intellectually can, we can instead laugh along with nature. What a wonderful prank to play on self-aware biological units! Indeed, what a beautifully creative exercise to engage the cognitive sapient with. As we will see, this could have very interesting implications for where things are eventually headed.

For now, we seem to have a functioning understanding of origin and why it happened. All that we are was born of, through reverse chronology, culture, biology, chemistry and physics. Some gaps and unresolved debates notwithstanding, our current picture of objective reality explains how certain natural processes, given a time of 14 billion years, can create homo sapiens out of a dense, hot ball of exotic particles. On the question of why, the data is in. Existence is infinite, without bounds. All permutations and combinations that can exist, do exist. Somewhere in this spectrum of infinity, non-existence also exists. But we are bound by the fact that we can only experience one body and one segment of spacetime. This gives rise to feelings of improbability, incredulity and the illusion of time. You cannot possibly know what non-existence is like, because you do not exist in it. If you did, you’d instead be wondering what existence was like, and why it wasn’t being tried instead of the dark, boring non-existence you were consigned to. Upanishadic thought delights in this dichotomy. There is both existence and non-existence, it tells us. Through existence, one knows non-existence. Through non-existence only can one imagine something like existence.

Another way to look at this is through seeing reality as the combination of intentionality and instantiation. While instantiation follows many cycles and is always in transition, intentionality is absolute and eternal. The questions of when and why can make sense in the case of instantiation, but being products of intentionality themselves, they make no sense when applied to it. The objective reality is neither improbable nor anything but eternal. But we can occupy only a bounded spacetime co-ordinate in one universe within one particular version of existence. Thus our consciousness expresses amazement at life, the universe and everything. It becomes clear then that to develop any further understanding on the matter, we will have to turn to the mind.